Bridging the ESG Finance Gap:

Demand and Supply-Side Constraints

Facing Nigerian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

September 2025

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| Introduction | |

| Internal Barriers | |

| External Barriers | |

| ESG Supply Side Analysis | |

| Industrialization and ESG Integration | |

| Governance | |

| Sustainability Risks and Management | |

| Financial Risk Categories | |

| Sustainability Disclosures | |

| Endnotes |

Bridging the ESG Finance Gap: Demand and Supply-Side Constraints Facing Nigerian Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (SMEs)

Introduction

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) form the backbone of economies globally, driving inclusive growth, job creation, poverty reduction, and innovation. Worldwide, SMEs make up around 90% of businesses and contribute over 50% of global GDP1. The impact is even more pronounced in Africa, where they represent over 90% of all businesses and provide nearly 80% of total employment2. In Nigeria, SMEs account for 96% of all businesses, contribute 48% to national GDP, and employ about half of the country's workforce3.

As a dominant force, SMEs are well-positioned to shape environmental, social, and governance (ESG) outcomes through their operations, workforce practices, and governance structures. Although individual SMEs have relatively modest operations, their collective environmental impact is substantial, particularly in terms of cumulative carbon emissions. On the social front, SME businesses often fall short in addressing labour standards, inequality concerns, or broader community development. For instance, Nigeria's recent minimum wage increased from ₦30,000 to ₦70,0004 has not been widely adopted in the SME sector due to affordability concerns or weak enforcement. In addition, structured corporate social responsibility initiatives are largely absent, even at a small scale.

From a governance perspective, many SMEs operate informally or semi-formally, with limited or no internal structure to support for decision-making, financial transparency, accountability, or regulatory compliance. This weak governance framework often leads to mismanagement, business fragility, and ultimately financial collapse. Considering that SMEs account for the majority of employment in Nigeria, such failures contribute significantly to rising unemployment and economic instability.

Nigerian SME Dominance

Global SME Comparison

| Region | Businesses (%) | Employment (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Global | 90% | 50% |

| Africa | 90% | 80% |

| Nigeria | 96% | 50% |

Despite their economic importance, Nigerian SMEs continue to face structural barriers to growth, particularly limited access to finance. According to PwC's 2023 MSME Survey, 69% of SMEs had not received any government grants in the preceding 24 months, with many citing bottlenecks and low trust in the formal banking system as key obstacles to financing access.5 These findings echo the World Bank's Doing Business report, which ranked Nigeria 131st out of 190 economies in terms of ease of starting a business6 .

SMEs, by virtue of their ubiquity, are both potential drivers of sustainable development and, conversely, sources of unsustainable practices due to systemic constraints. It is important to address their financing-access gap, especially through solutions aligned with ESG principles. Strengthening SMEs' ESG practices is not only essential to advancing sustainability but also to strengthening the long-term resilience and competitiveness of economies like Nigeria.

Concurrently, the financial ecosystem is undergoing a structural shift towards achieving the Sustainable Development Goals7. ESG considerations are now central to capital allocation, driven by international climate commitments (such as the Paris Agreement8), growing investor interest, and the rise of sustainability-linked financial instruments. Financial institutions including banks, DFIs, venture capitalists, and insurers are now embedding ESG factors into their lending and investment frameworks. This shift, however, requires all borrowers, including SMEs, to demonstrate credible sustainability credentials through robust ESG metrics, climate-related disclosures, and demonstrable alignment with social or environmental goals.

This convergence creates a paradox. On one hand, Nigerian SMEs face a deep and persistent financing gap, worsened by macroeconomic instability, regulatory uncertainty, and limited capacity to scale. On the other hand, there is a growing pool of sustainability-linked capital seeking credible investment opportunities in developing markets. These include impact and blended finance instruments, as well as sustainable finance products such as green, social and, sustainability-linked loans. Yet, Nigerian SMEs have largely been excluded from this momentum systemic barriers continue to restrict their access to such financing options.

On the demand side, SMEs face internal barriers such as the absence of ESG-related data or metrics, the lack tailored ESG standards, and limited awareness or capacity to integrate ESG considerations into daily operations or long-term strategy. Most SMEs also lack the technical resources to track, measure, or report on ESG performance and, these are often required by sustainability-focused lenders and investors. On the supply side, financial institutions are developing internal ESG frameworks in response to evolving regulatory requirements and international standards. However, these frameworks are typically designed for large corporates and rarely account for the unique constraints of SMEs. As a result, sustainable finance products are often too complex, rigid, or inaccessible for SMEs to access effectively. Moreover, government and market-level interventions intended to support MSMEs often prove ineffective or remain underutilized.

For example, although Nigeria has introduced initiatives such as the National Collateral Registry, the Development Bank of Nigeria, and the Bank of Industry's energy-efficient loan schemes, their overall impact remains limited. The PwC MSME Survey (2024) further highlights priority areas for reforms, including: (i) improving access to affordable finance; (ii) streamlining regulatory burdens; (iii) enhancing MSME adaptability to shifting market conditions; and (iv) accelerating digital and green transformation through targeted incentives9.

| Demand-Side Challenges (SMEs) | Supply-Side Challenges (Financial Institutions) |

|---|---|

| Lack of ESG-related data/metrics | Frameworks designed for large corporates |

| No clear/applicable ESG standards | Do not consider SME-specific constraints |

| Limited knowledge/capacity for ESG integration | Too complex, rigid, or inaccessible products |

| Few technical resources for ESG reporting | Dependence on reliable data SMEs lack |

The disconnect between both sides has contributed to a significant gap in SME-tailored sustainability finance products, leaving a large segment of the private sector excluded from Nigeria's transition to a greener and more inclusive economy. This exclusion is particularly concerning given Nigeria's commitment to achieving net-zero emissions by 2060. SMEs will be central to this transition—particularly in energy, agriculture, manufacturing, and transport sectors. Yet without practical and scalable pathways to align with ESG objectives, they risk being left behind in the evolving green economy.

This paper – the first in a three-part series – provides a comprehensive analysis of both supply-side and demand-side opportunities and challenges facing Nigerian SMEs in their pursuit of sustainability-linked capital. It seeks to highlight the disconnect between financier expectations and SME realities, and to propose actionable recommendations to strengthen SME access to sustainable finance.

DEMAND SIDE

Despite the expanding pool of sustainability-linked capital, Nigerian SMEs remain largely excluded from accessing it, due to persistent demand-side constraints. As global and domestic capital flows increasingly prioritise ESG considerations, SMEs face growing expectations that they are often unprepared to meet.

This exclusion chiefly stems from structural and institutional challenges within the SME segment itself. These demand-side barriers can be grouped into two categories:

Internal Barriers

- Limited ESG awareness

- Weak reporting capacity

- Resource constraints

External Barriers

- Inadequate ESG infrastructure

- Insufficient incentives

- Fragmented guidance frameworks

Together, these factors undermine SME readiness and credibility, restricting their participation in sustainable finance landscape and widening the gap between the availability of capital and the ability to access it.

INTERNAL BARRIERS

Limited Awareness:

Many SMEs remain unaware of ESG-linked finance and its associated reporting requirements. This knowledge gap extends to critical concepts such as ESG metrics, climate risk disclosures, and performance-based loan covenants.10 A 2023 global survey revealed that while 83% of SMEs recognise the importance of sustainability, only 8% actually report on sustainability issues, underscoring the gap between recognition and practical integration.11 In Nigeria, insufficient awareness is consistently cited as a key reason for limited sustainability reporting, with many SMEs lacking the necessary knowledge and resources to track and disclose their ESG performance.12 To address this, initiatives led by organizations such as the UN Global Compact Network Nigeria, in collaboration with the Financial Reporting Council of Nigeria (FRC) and Integrity Organisation, have introduced guidelines such as the Small and Medium Enterprises Corporate Governance Guidelines (SME-CGG).

The Awareness-to-Action Chasm

Recognize Importance

Take Action

Key Insight: This stark gap highlights that awareness alone is insufficient; SMEs need practical tools, simplified processes, and clear incentives to act.

Poor Reporting Capacity:

Few small firms have the systems required to track non-financial performance. A global study revealed that only about 9% of SMEs operate formal sustainability-reporting programmes, largely due to constraints of time, expertise, and budget.13 Without baseline data on emissions, water use, waste generation, employee metrics, or governance practices, SMEs are unable to meet the minimum entry requirements for green bonds, sustainability-linked loans, or climate funds.

The Vicious Cycle of Data Deficiency

1. Data Gaps

No systems to track ESG

2. Hindered Reporting

Cannot meet standards

3. Limited Finance

Lenders can't verify

4. No Investment

Can't afford new systems

Key Insight: Breaking this self-reinforcing cycle requires an external intervention focused on providing foundational data infrastructure and literacy.

Resource Constraints:

In Nigeria, this gap is even more pronounced. A 2023 industry study concluded that "the vast majority of SMEs do not collect or manage any form of ESG-related data."14 Reported challenges include (a) lack of consistent and reliable data on ESG metrics; (b) difficulty in measuring and quantifying social and environmental impacts; and (c) financial and resource constraints.15 The informal nature of many Nigerian SMEs further exacerbates this issue, with some lacking even basic financial records. This creates a vicious cycle: data gaps hinder reporting, poor reporting limits access to sustainable finance, and lack of financing prevents investment in the very systems needed to improve reporting. Addressing this requires solutions that build fundamental data infrastructure and literacy, including business formalisation and digital transformation, which can then be leveraged for sustainability reporting. The complexity and fragmentation of current reporting regimes also highlight the need for simplified, standardized, and interoperable reporting frameworks tailored specifically for SMEs.16

Limited Staff and Tools:

Most SMEs lack in-house ESG specialists and adequate data-management tools, making the collection and verification of ESG indicators difficult. Reports indicate that the vast majority of SMEs neither employ sustainability experts nor use automated systems, which prevents them from responding effectively to lenders' data requests.17 As a result, they struggle to produce the disclosures necessary for banks or investors to assess sustainability performance, conduct due diligence, or structure performance-based pricing. Addressing this requires two parallel solutions. Firstly, the development and promotion of accessible, affordable, and user-friendly digital tools for ESG data collection and reporting – tools that are localised, intuitive, and easily integrated into existing SME workflows. Achieving this will require collaboration between technology providers, financial institutions, and SME-support organizations. Secondly, beyond technological tools, the human-capital gap within SMEs must be tackled through systematic upskilling of existing staff in sustainability principles and practices, complemented by accessible pools of external advisory support.

High Uncertainty:

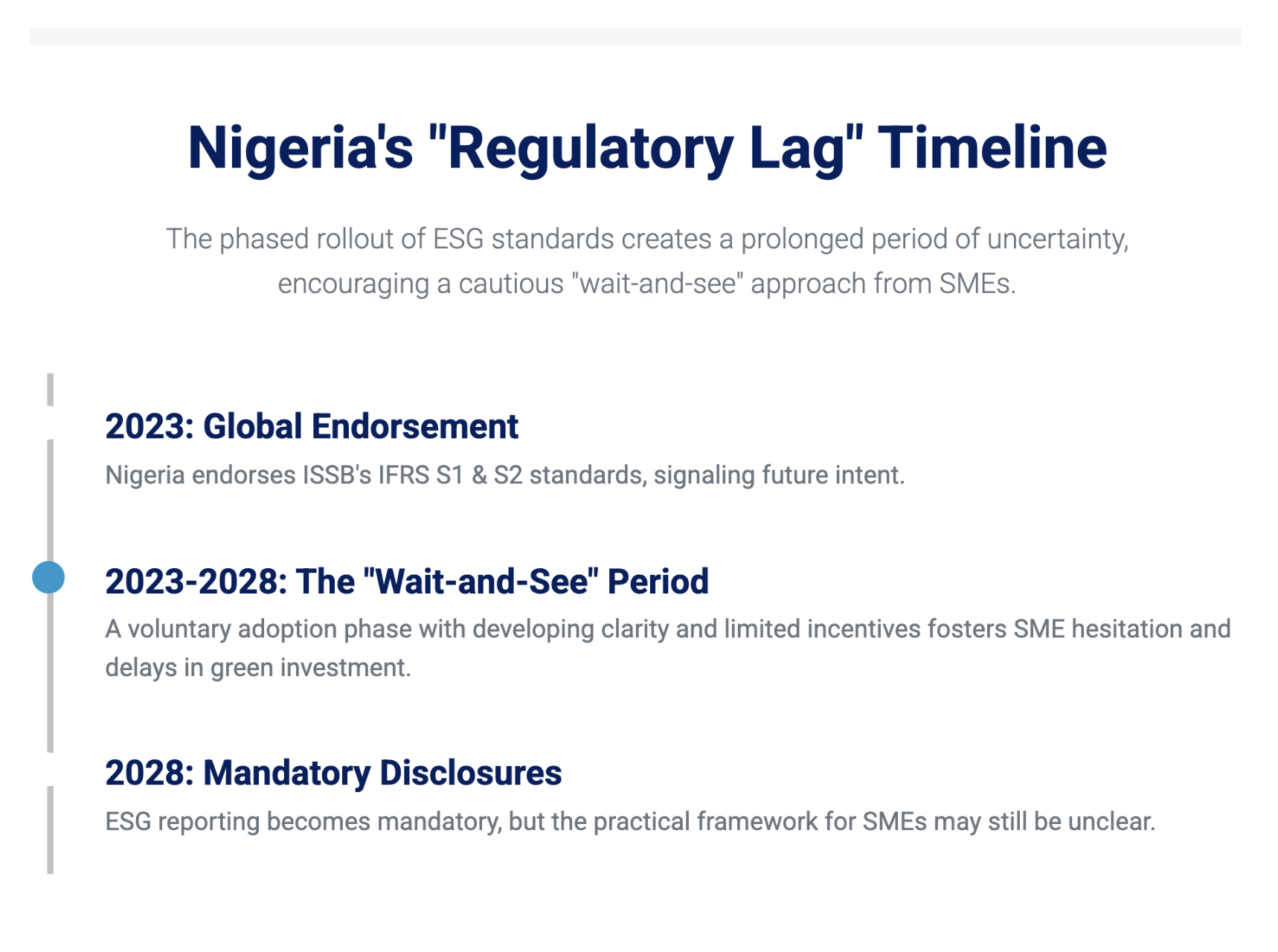

SMEs also operate in highly volatile markets characterised by policy shifts and economic instability, which the OECD identifies as "one of the greatest barriers" for SMEs in pursuing green initiatives18. SMEs often hesitate to invest in sustainability due to concerns about uncertain returns or future regulatory changes. A 2025 World Economic Forum (WEF) report found that 47% of manufacturing SMEs cited "policy uncertainty" as a significant barrier19. While Nigeria has endorsed the adoption of ISSB's IFRS S1 and S2 standards with mandatory ESG disclosures from 2028, the phased implementation implies a period of voluntary adoption where clarity may still be developing20. Broader macroeconomic developments such as fuel subsidy removals and exchange rate reforms, further contribute to instability, undermining SMEs' ability for long-term planning, including sustainability investments. This "regulatory lag" fosters a "wait-and-see" mentality.

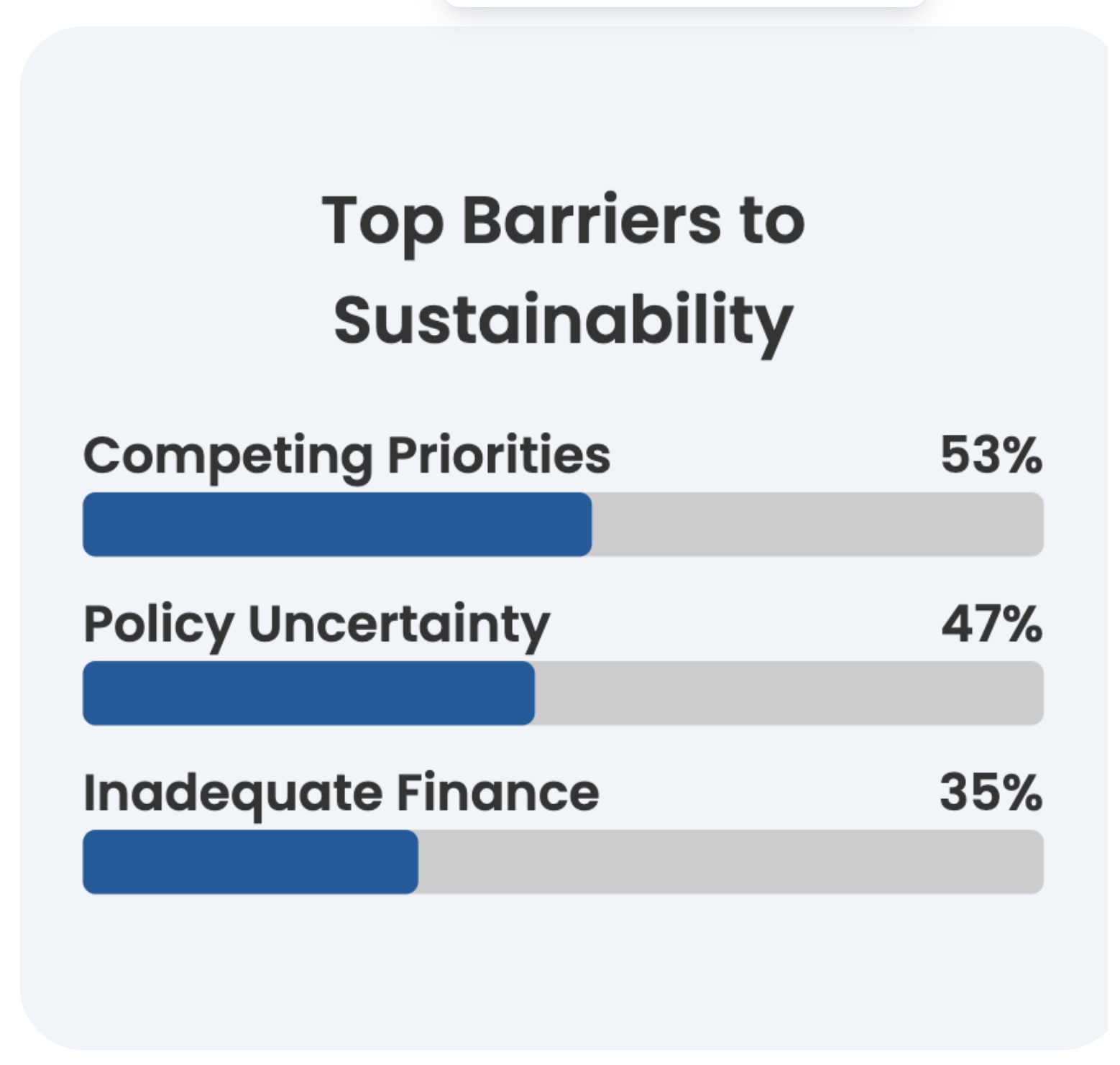

To counter this, clear, consistent, and long-term policy signals from governments are critical, including a stable regulatory environment, well-defined incentives, and a transparent roadmap for sustainability integration. Furthermore, the WEF survey also highlights that 53% of SMEs identify competing priorities such as cost pressures and business expansion as the main obstacles. This suggests that even with regulatory clarity, immediate financial and operational constraints make long-term sustainability investments a lower priority .

Short-term Survival Focus:

Operating on tight margins, SMEs tend to prioritize immediate needs over long-term sustainability, often putting ESG initiatives on the back burner due to time and cash pressures. In practice, this means survival needs often supersede strategic green planning, and ESG becomes a "nice to have" rather than a core business priority, especially when its return on investment (ROI) is uncertain or indirect. PwC's MSME Survey 2024 in Nigeria found "inadequate access to finance" as the number one challenge for 35% of businesses, while over 50% reported falling sales due to high prices and weak consumer spending power21. Other reports highlight additional pressures such as "obtaining finance, finding customers and infrastructure deficits"22. These factors directly explain why short-term cashflow and immediate survival dominate SME priorities.

External Barriers

Beyond these internal limitations, SMEs are also constrained by systemic factors within the broader ESG and financial ecosystem. These external forces lie outside the direct control of the SME yet significantly impact their ability to adopt sustainable practices and secure green financing.

Weak ESG Ecosystem:

The broader support infrastructure for SMEs in the ESG space is significantly underdeveloped. Most markets lack sufficient SME-focused ESG scores, certifications, or verifiers23. This leaves proactive SMEs unable to effectively "highlight their sustainability credentials" because there are no accessible, credible ratings or audit services tailored for small companies. While global assurance firms cater to large corporations, Nigerian SMEs face a "credibility gap". Due to the absence of a government-endorsed or widely recognised ESG certification framework. As a result, even committed SMEs struggle to access green finance, since lenders lack standardized, verifiable methods of assessing their sustainability performance. Addressing this gap requires a simplified, credible, and affordable ESG assessment and certification mechanisms, potentially delivered through local partnerships, digital platforms, or tiered certification systems calibrated to SME resources.

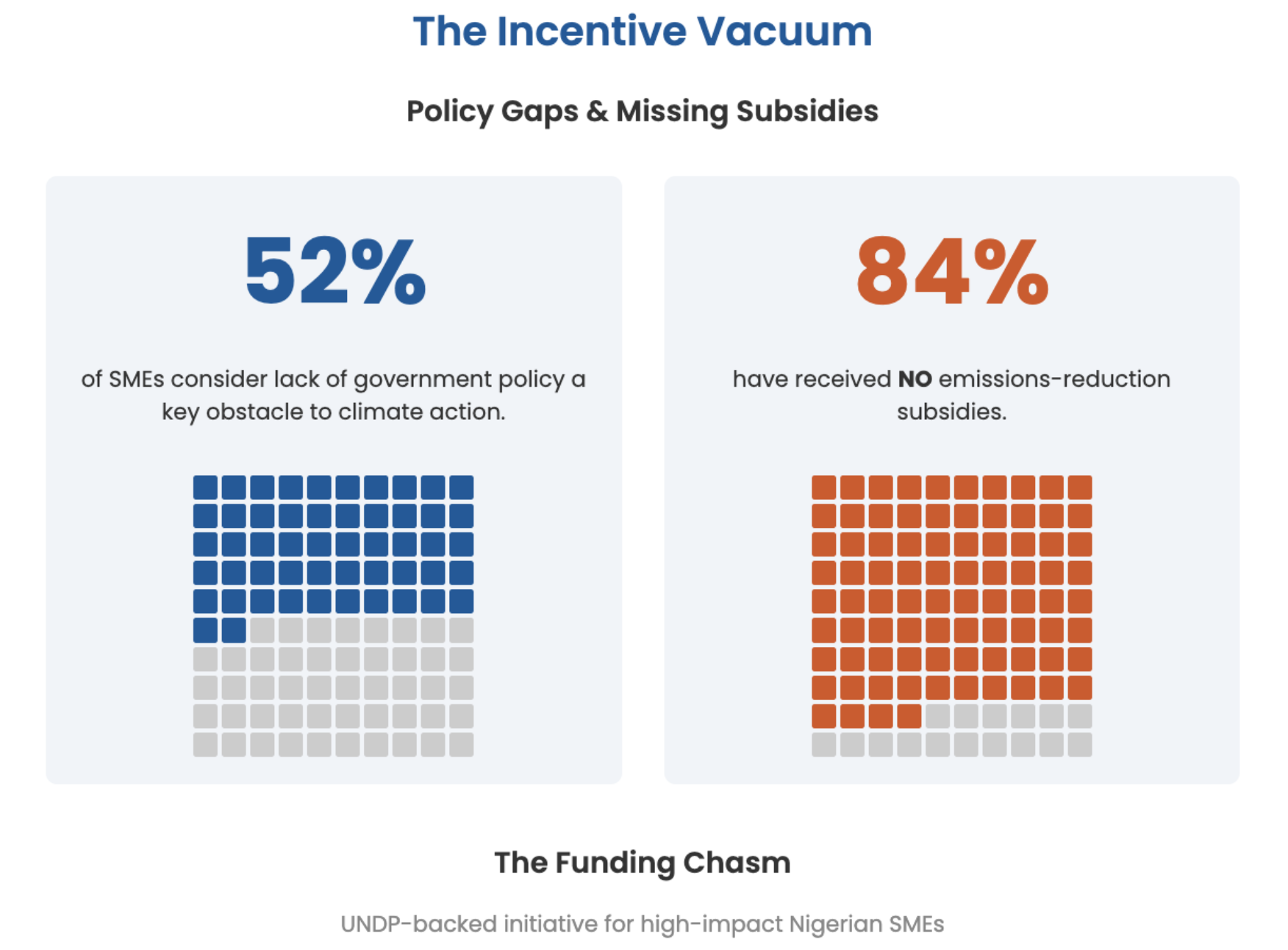

Sparse Incentives:

Public incentives for SME "greening" remain limited and inconsistent. Surveys show that 52% of SMEs consider the lack of government policies or incentives a key obstacle to climate action, while 84% report receiving no emissions-reduction subsidies24. While governments are enacting sustainable finance policies (e.g., Nigeria's Climate Change Act), a significant gap exists between high-level policy commitments and the practical, on-the-ground experience of SMEs, suggesting policies are not effectively communicated, accessible, or tailored to their specific needs. Without tax breaks, grants, or concessional schemes, SMEs see little financial gain from sustainability investments. In Nigeria, evidence suggests that SME access to ESG-linked finance is negligible. Development initiatives have mobilized only limited funds for a handful of SMEs; for instance, a UNDP-backed program identified 25 high-impact Nigerian SMEs combined sustainable-finance needs of $175 million but mobilized just $15 million for three ventures25. This mismatch illustrates how most bankable, sustainability-aligned SMEs cannot easily tap into available green or SDG-linked financing, often leaving them with standard lending at higher rates26. Closing this gap requires strong "pull" factors—targeted tax reliefs, concessional financing and non-financial incentives, beyond mere "push" regulations, to make sustainability an immediate business advantage, rather than just another compliance burden27.

Fragmented Information

Guidance on sustainable finance is often scattered, leaving SMEs to navigate a confusing patchwork of standards and disclosure requirements. The OECD notes that SMEs urgently need better frameworks and tools to bridge sustainability data gaps when seeking finance. In practice, each lender or donor often demands different disclosures, creating an "information overload" paradox: SMEs simultaneously lack awareness of relevant ESG finance tools yet face an overwhelming flood of disparate requirements. This leads to paralysis or misdirected efforts, or outright disengagement. A centralized, harmonized guidance system is therefore essential. This could take the form of a national portal or advisory hub that consolidates requirements, offers standardised templates, and clarifies which frameworks apply to different SME segments. Standardised methodologies, simplified independent verification systems, and trusted data protocols would further build lender confidence in trust in SME-generated ESG data.

While demand-side barriers highlight the limitations within SMEs and their immediate environment, the challenges are equally pronounced on the supply side. Financial institutions, investors, and regulators often lack the tools, incentives, and frameworks to originate and scale ESG-linked finance tailored to the realities of Nigerian SMEs. The next section, therefore, examines the structural, institutional, and commercial constraints that hinder the flow of sustainable capital—highlighting why even willing capital providers struggle to connect with the SME segment in a meaningful and scalable way.

SUPPLY SIDE

For SMEs, accessing sustainable finance is not only a question of demand but also of how finance is supplied. Even when SMEs demonstrate viable business models and a willingness to adopt sustainable practices, their financing prospects ultimately depend on the products, risk appetites, and compliance obligations of financial market participants ("FMPs").

Sustainability objectives can only be achieved if private capital is effectively channelled towards sustainable investments, primarily through FMPs operating in the financial services market (the "Market"). In practice, this may involve a financial institution ("FI") offering products such as concessional or sustainability-linked loans to a corporate borrower ("counterparty"). These products are ultimately funded by end-investors who allocate capital for sustainability purposes. This structure creates an agent-principal relationship: FIs act as agents of the end-investors and owe fiduciary duties to ensure that investments align with stated sustainability objectives. As part of these obligations, FIs must (i) conduct adequate due diligence including, sustainability risk assessments before making investments; (ii) integrate sustainability considerations into investment decision-making and governance; and (iii) provide pre-contractual and ongoing disclosures to investors28.

To safeguard against 'greenwashing', end-investors carefully scrutinise FMPs, avoiding those that misrepresent financial products as sustainable without meeting environmental standards. FMPs are therefore, required to explain and demonstrate how the activities they finance contribute to environmental or social objectives.

Sustainability (ESG) Risks and Management Considerations for the Supply Side

For FIs, sustainability risks are not abstract concerns but material financial risks that directly affect credit quality, solvency, and long-term profitability. Sustainability risks (or ESG risks) arise when environmental, social, or governance factors negatively affect the financial performance of counterparties, whether corporate borrowers, sovereigns, or individuals, and, through them, the balance sheets of financing institutions29.

Transmission Channels and Risk Drivers of ESG Risk

ESG risks typically materialise through established financial risk categories: credit, market, liquidity, operational, and reputational risk. The impacts are transmitted to FIs via their borrowers, clients, and invested assets30 through channels such as: (a) reduced profitability and cashflow of counterparties; (b) declining collateral and asset values (e.g., real estate, stranded assets); (c) deterioration of asset performance; (d) increased compliance and legal costs; and (e) loss of customer and investor confidence (reputational damage)31.

Environmental Risk Drivers

Environmental risks arise from both physical risks (direct consequences of climate change and environmental degradation) and transition risks (shifts in policy, technology, or market behaviour during the transition to a sustainable economy)32.

- Physical risks: Floods, droughts, and pollution can reduce counterparties' productivity and profitability. For example, a borrower in the agricultural sector affected by oil spill contamination may face declining yields, higher default probability, and greater credit risk for the lending FI.

- Transition risks: Policy shifts such as carbon taxes or stricter environmental regulations can erode profitability for carbon-intensive businesses. Technological change and consumer preference shifts (e.g., away from fossil fuels) can lower the value of collateral and lead to stranded assets33.

Social Risk Drivers

Social risks stem from how counterparties manage relationships with their workforce, communities, and consumers34. Key issues include labour rights, diversity and inclusion, working conditions, and access to essential services35. Further, violations of labour rights or community relations can trigger litigation, reputational damage, or operational disruption. For instance, the COVID-19 pandemic illustrated how systemic social shocks affect creditworthiness: widespread lockdowns reduced SME revenues, raised unemployment, and increased credit risks across bank portfolios. For Nigerian SMEs, these risks are magnified given limited resilience and weaker labour protections.

Governance Risk Drivers

Governance factors affect the transparency, integrity, and long-term sustainability of counterparties. Weak governance undermines financial performance and increases FI exposure 36 . Common drivers include poor internal controls, inadequate financial reporting, lack of board independence, and corruption. Nigerian SMEs face heightened governance risks due to informality, weak disclosure practices, and limited oversight capacity. Failures in corporate governance can escalate into broader reputational crises, especially since economic crim such as bribery, corruption, or money laundering scandals attract regulatory and market sanctions37.

Litigation (Liability) Risk

Litigation risk cuts across environmental, social, and governance issues. Counterparties may face lawsuits for environmental damage, discriminatory labour practices, corruption, or regulatory breaches. Such claims can impair counterparties' financial performance, reduce their ability to repay, and create direct financial and reputational exposure for FIs.

FI Risk Management Obligations

To mitigate sustainability risks, FIs are expected to embed ESG risk considerations within their overall business strategy; define and disclose their ESG risk appetite; establish clear governance structures with assigned responsibilities for ESG risk management; and maintain robust risk management frameworks capable of identifying ESG exposures, addressing data and methodology gaps, and stress-testing resilience. By aligning their investment and lending activities with ESG risk principles, FIs not only protect their balance sheets but also reinforce the integrity and scalability of the broader sustainable finance ecosystem.

Assessment of Financial Risk Categories Occasioned by Sustainability Risks

Operating in fast-evolving markets, FIs must carry out regular assessments to identify both current and prospective impacts of ESG factors on counterparties or invested assets. This requires the integration of ESG risks into their business strategies, internal governance arrangements and overall risk management frameworks.

According to the EBA Report, three main approaches are used in assessing ESG risks – the portfolio alignment method, the risk framework method, and the exposure method 38. Of these, the exposure method is regarded as the most practical. It involves a direct assessment of individual counterparties and exposures and covers all three aspects of ESG. This method evaluates the ESG attributes of a counterparty or exposure at company level, calibrated by granular sectoral characteristics, and the results are then used to complement the standard assessment of financial risk categories 39. Methodologies employed under this approach include ESG ratings provided by specialised rating agencies, ESG evaluations from credit rating agencies, ESG evaluation models developed in-house by banks for, and ESG scoring models created by asset managers or public data providers 40. However, as noted in the demand-side section above, SMEs frequently lack the data and transparency necessary for this exposure-based assessment, which makes it particularly challenging for FIs to extend sustainable finance products to them.

FIs Treatment of Financial Risk Categories Occasioned by ESG Risk

FIs apply forward-looking metrics to assess how ESG factors affect standard financial risk categories, especially for long-term financing exposures such as real estate loans41.

- Credit and Counterparty Risk

FIs are required to assess the impact of ESG risk on its credit risk for each portfolio or counterparty, incorporate these risks into their risk appetite statements, and integrate them into loan origination and ongoing monitoring. The ESG profile of a counterparty is therefore evaluated both at inception and throughout the duration of the relationship. - Market risk

End investors increasingly apply negative screening policies based on ESG considerations. As a result, FIs must closely monitor the impact of ESG risks on their market risk position, adopting comprehensive ESG market risk policies that include due diligence requirements and ESG checklists. In circumstances where ESG data is unreliable or unavailable, many FIs apply negative screening and exclude such investments altogether42. - Operational & Reputational Risk

FIs must carefully evaluate the extent to which ESG-related operational exposures could result in reputational or legal damage, ensuring consistency between their public disclosures and internal practices in order to mitigate the risk of greenwashing. - Liquidity and Funding Risk

ESG risks can also affect liquidity and funding positions. In the short and medium term, liquidity risks may arise from unexpected net cash outflows linked to environmental or social crises43, while in the medium to long term, reputational or sustainability concerns may impair market access and limit the stability of funding profiles. FIs are, therefore, required to assess liquidity risks across varying time horizons to ensure resilience to ESG-related shocks.

Challenges in Assessing Sustainability Risks

To integrate ESG risks effectively, FIs must calibrate assessments at the counterparty level, taking into account sector-specific characteristics and combining qualitative and quantitative indicators44. In practice, this often requires the use of data from dedicated ESG providers or partnerships with public initiatives. However, several challenges persist. ESG data for counterparties such as SMEs or companies in emerging markets is often scarce, discouraging investors from allocating capital to sustainable products linked to these entities. Even when data is available, it is frequently inconsistent, incoherent, or insufficiently comparable, making it difficult for FIs to translate ESG information into meaningful expectations about financial performance45 or the resilience of business models46. Moreover, most companies still do not integrate ESG factors into their reported data, which limits the ability of FIs to incorporate these considerations into critical risk parameters such as probability of default or loss given default47.

Sustainability Disclosures for the Financial Services Sector

FIs that provide financial products, as well as market participants that promote products with sustainability objectives are required to make comprehensive disclosures. These disclosures build end-investor confidence by clarifying the degree of sustainability investment, with most disclosure regimes placing emphasis on environmental considerations.

These disclosures typically cover (i) the environmental objectives to which underlying investments contribute (ii) how and to what extent criteria for sustainable economic activities are applied, including ESG risk management and governance practices; and (iii) the extent to which sustainable products invest in activities meeting the sustainability criteria48.

Disclosure regulations such as the SFDR and the Taxonomy Regulation impose obligations specifically on FIs, market participants, and issuers of sustainable products49 requiring them to provide both pre-contractual and ongoing disclosures to end-investors50. These frameworks aim to reduce information asymmetries in the principal-agent relationship by clarifying how sustainability risks are integrated, how adverse sustainability impacts are considered, and how environmental or social characteristics are promoted51. They also strengthen transparency, enhance investor protection, and provide comparable benchmarks on the proportion of investments aligned with sustainable economic activities.

At the EU level, regulations establish technical screening criteria regime52 for environmental objectives, notably climate change mitigation, with provisions for regular updates to reflect evolving science and technology53.

Disclosure Obligations

Nigeria does not yet have a sustainability disclosure regime specific to the financial services sector, Section 24(1)(a) of the Climate Change Act requires private companies with more than 50 employees to adopt measures aligned with national annual carbon-emission reduction targets under the National Climate Change Action Plan54.

By contrast, FMPs subject to EU laws must comply with the Sustainability Finance Disclosure Regulation and the Taxonomy Regulation (together, the "EU Disclosure Regulations")55. The EU Disclosure Regulations require market participants to publish and maintain disclosures on their websites, covering the principal adverse impacts of investment decisions on sustainability factors and the due diligence policies applied56. They also prescribe detailed pre-contractual disclosures57, including environmental objectives58, criteria for assessing environmentally sustainable activities59, the nature and details of information to be disclosed60, activities contributing to climate change mitigation61, and enabling activities62. Importantly, EU member states retain discretion to adopt more stringent disclosure requirements for market participants headquartered in their jurisdictions63.

Disclosure Obligations: Nigeria vs EU

| Aspect | Nigeria | EU |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Companies> 50 employees | All Market Participants |

| Requirements | Carbon reduction measures | Comprehensive ESG disclosures |

| Detail Level | Basic | Highly Detailed |

| Enforcement | Developing | Strict |

Conclusion

The financing divide limiting Nigerian SMEs' access to ESG-linked capital is a dual challenge rooted in both the supply and demand dynamics. On the demand side, SMEs face significant internal and external barriers that create a persistent credibility gap, leaving them unable to satisfy the stringent reporting and governance standards required by financial institutions. On the supply side, Fis, bound by fiduciary duties to end-investors and evolving regulations, apply ESG risk assessment and disclosure frameworks that are ill-suited to the informal and data-scarce reality of the Nigerian SME sector.

The disconnect between SMEs lacking the capacity for comprehensive ESG reporting and FIs mandated to require it, remains the central constraint to mobilizing green capital. Bridging the gap will require a coordinated, multi-stakeholder effort to tackle systemic issues such as data scarcity, fragmented guidance, and the misalignment of international standards and local market realities. Only through coordinated action among regulators, FIs, investors, and SME support networks can Nigeria establish a practical and inclusive sustainable finance ecosystem that channels ESG-linked capital to small businesses.

Endnotes.

Bridging the Financing Divide

Contact Information

Banwo & Ighodalo

September 2025